St Patrick’s Catholic Cemetery is situated at the junction of Church Street and Pennant Hills Road, North Parramatta. Documentary evidence shows that on the morning of the 29 September 1823, Catholic Chaplain, Rev Joseph Therry, notified Governor Thomas Brisbane of his intention to consecrate the Catholic burial ground in Parramatta at 12 o’clock that day [1]. The establishment of a dedicated cemetery was a significant step for the Catholic Church in the colony for it afforded its congregation the freedom to bury their dead according to the rites of their faith.

The cemetery was certainly in use by 1824 when three individuals were interred. Thomas Nugent in April, Philip Reilly in June and Thomas McKenna in August of that year [2]. Of these three, only the location of the grave of Philip Reilly remains unmarked today. Records show that a total of 2,155 burials were made between 1824 and 1971, however only 400 marked graves remained in 1979 recording the locations of about 800 people [3].

Founded in the main by Irish Catholics, the cemetery soon became the last resting place of Individuals from many levels of society and of immigrants from across the world. Many of those interred in the first thirty years of the cemetery had died in one of the many public institutions in Parramatta. An entry in the St Patrick’s Burial Register at the end of 1840 noted “there died in the Factory 55 male and 36 female children” [4]. Sadly, the locations of their graves were unmarked and are therefore unknown.

It is unclear whether any Aboriginal people were buried in St Patrick’s although some entries in the parish register were recorded as one single name which may indicate that the deceased was an Aboriginal. The inclusion of the word ‘native’ in some entries may refer to an Aboriginal person or could simply mean “born in the colony”.

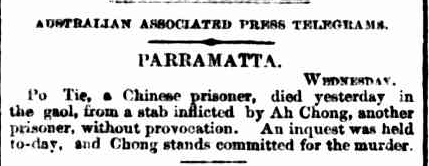

The cemetery includes several members of the Chinese community including Po Tie. Tie was stabbed by a fellow prisoner in Parramatta Gaol on the 19 January 1876. He had been sent to Parramatta from Berrima Gaol in February 1873 under sentence of seven years on the road gangs.

The inquest heard that the fatal wound was inflicted by Ah Chong with the intent to do grievous bodily harm. No provocation for the murder could be ascertained but the perpetrator had been previously tried at Mudgee for a similar offence [5]. The grave of Po Tie is unmarked.

Bridget Gillorley of Parramatta married into a Chinese family when she wed John Shying in October 1842. She died a short time later on the 29 January 1845 aged 56 years. Other members of the Shying family were interred in St John’s Anglican Cemetery, Parramatta, but Bridget was buried with Daniel O’Neil (the step-father to the first wife of John Shying, Sarah Jane Thompson) who had died on the 18 March 1842 aged 65 years [6].

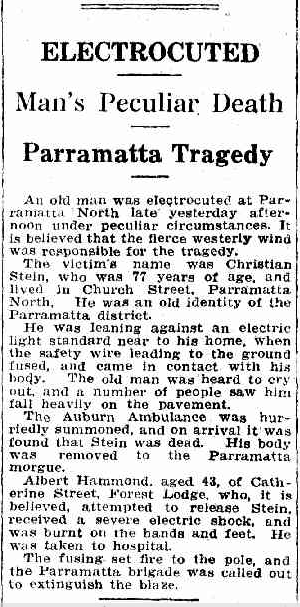

Within the cemetery are many from European countries such as Germany, Italy and France. The Stein family for example was one of six families of vineyard workers brought to the colony by John Macarthur to tend his vineyards along the Parramatta River [7].

Christian Stein, the son of Jacob Stein and Anna Maria Stein (also interred in St Patrick’s) was born in Narellan in 1845 and died as a result of an unusual accident in 1923, aged 77 years. The details were reported in the Daily Telegraph stating that he “was leaning against an electric light standard near to his home, when the safety wire leading to the ground fused, and came in contact, with his body” [8].

The dedication of St Patrick’s Cemetery was also important in providing a fitting setting for the burial of the clergy of the parish. The Mortuary Chapel within the grounds of the cemetery was dedicated to St Francis of Assisi in August 1844 [9]. The Rev Dean Nicholas Joseph Coffey who was responsible for the building of the chapel was buried beneath the floor of the chapel on the 13 November 1857.

Rev Coffey was an Irish Franciscan priest who arrived in the colony in 1839 and served in Melbourne prior to coming to Parramatta. During his term of office as parish priest between 1852 and 1857, the third St Patrick’s Church was completed. A richly ornamented memorial tablet was placed in St Patrick’s Church of the time and this memorial has been positioned in the current St Patrick’s Cathedral in Parramatta. Several parish priests including Monsignor Thomas O’Reilly, Monsignor Joseph John McGovern and Dean John Rigney were also buried within the chapel building [10].

In some instances, the true age of the deceased at the time of death is somewhat of a mystery. Originally from Dublin, Ireland, Ann Bellamy (nee Fay or Foy) was convicted of a felony and arrived in the colony as a convict with a seven year sentence aboard the Marquis Cornwallis in February 1796, giving her age as 42 years [11].

Ann Fay married William Bellamy, also a convict, in 1797 at St John’s Parramatta. The couple took up residence in the Pennant Hills area obtaining several grants of land in the area. Bellamy Road, West Pennant Hills is named after Bellamy whose farm was in the vicinity [12].

Ann Bellamy served her sentence without incident and earned her Certificate of Freedom which was granted on 9 February 1811 [13]. She died in January 1843 and according to her age on arrival she would have been aged 89 years. Her headstone is inscribed “100 years” and the parish register records her age as being 103 years [14]. There is no obvious explanation for such a disparity.

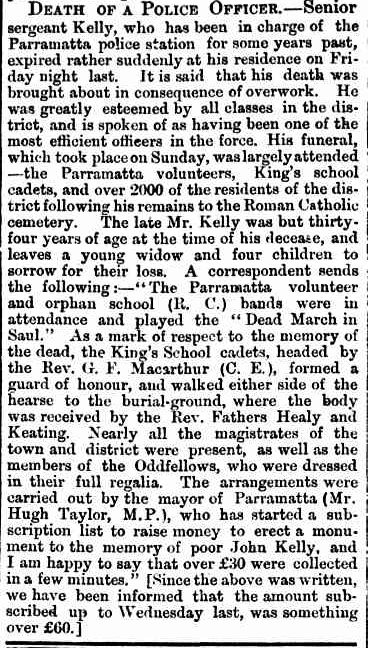

One of the most substantial sandstone monuments in the cemetery was dedicated to Senior Sergeant John Kelly who died on the 17 October 1873 aged 34 years. This memorial was erected by the citizens of Parramatta to express their esteem and respect for the work of this young police officer. It was said that “his death was brought about by the consequence of overwork” [15].

Kelly was credited with assisting in the solving of the Parramatta River murders in 1872. George R. Nicholls and Alfred Lester duped several newly-arrived immigrants with the promise of work, however the pair would steal their victim’s often meagre possessions and throw their body in the river weighed down with stones. Several bodies were found washed up on the banks of the river. This crime shocked the community.

On hearing of Kelly’s death the Mayor H Taylor esquire instigated a fund to erect a suitably handsome memorial over the grave of the much admired senior sergeant. In addition to his police duties Kelly was also employed by Parramatta Municipal Council as an Inspector of Nuisances and following his death his outstanding wages were to be paid to his widow, Julia.

Three of John Kelly’s children with Julia are also buried in St Patrick’s. A son, James William aged two years and a daughter, Julia aged one were both buried in St Patrick’s in 1868 while another daughter, Catherine Magdalene was born a couple of months after her father’s death but she only lived for eight months, passing away in August 1874 [16].

One of Parramatta’s rather colourful characters also lies buried in St Patrick’s. John Hodges arrived in the colony as a convict aboard the Duke of Portland in July 1807. Stories abound regarding his exploits including that he escaped detention and headed for Timor only to be recaptured and returned to the colony to complete his sentence [17].

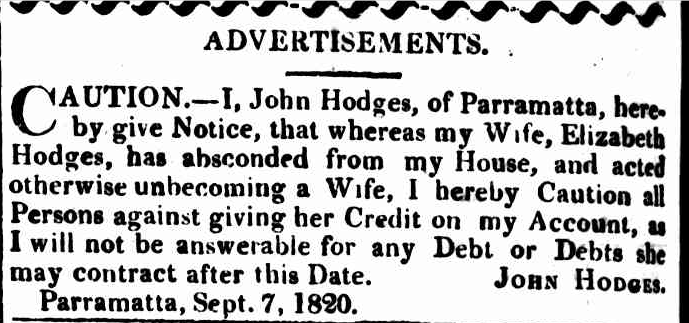

Married to Elizabeth Williams on the 31 December 1810 in St John’s Parramatta his partnership with Elizabeth appears to have foundered by 1820 when he placed the following advertisement in the classified advertisements in the Sydney Gazette [18]. It is not known whether Elizabeth was reconciled with John and if she enjoyed the comforts and conveniences of his comfortable two storey brick home which he was constructing at that time.

Hodges had gained his Ticket of Leave in 1813 and was able to obtain a publican’s licence in 1818 which was revoked in 1821 [19].

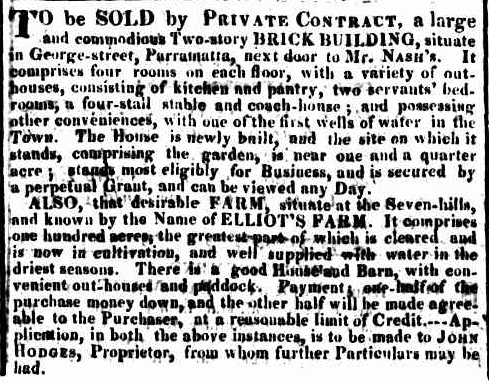

Leasehold properties which could later be converted to grants were offered by Governor Macquarie on the condition that a substantial brick building was erected on the land. Hodges acquired a lease and in 1819 commenced construction of the building on the corner of Marsden and George Streets today known as ‘Brislington’. In June 1823, Hodges’ building was valued at more than £1000 which enabled the lease to be converted into a grant [20].

The story goes that Hodges won the £1,000 required to construct such a substantial building in a card game which took place at the old Woolpack Inn which goes to explain where a man of little means was able to afford such as large property. Hodges had many encounters with the authorities during his lifetime and by 1825 he was again in trouble. It was necessary for him to dispose of his properties [21].

The following advertisement appeared in the Sydney Gazette on the 14 April, 1825 “a large commodious two storey red brick building comprising four rooms on each floor with a variety of outhouses”.

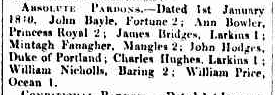

Hodges passed away on 14 June 1849 aged 67 years having received his absolute pardon only five years before [22]. He was interred in a substantial sandstone altar monument on a stepped base.

The cemetery was transferred to Parramatta City Council on 22 May 1975, pursuant to the NSW Conversion of Cemeteries Act 1974. The City of Parramatta continues to fulfil its role in the management and conservation of this significant cemetery. The lives and stories of the people interred within are woven into the fabric of Parramatta society and it is important to recognise their contribution to the history of the region.

![]()

Cathy McHardy, Research Assistant, Parramatta Heritage and Visitor Information Centre, 2021

References:

[1] State Archives and Records NSW, Colonial Secretary Correspondence, Rev J J Therry to Sir Thomas Brisbane 23 September 1823, Reel 6065.

[2] Dunn, J. The Parramatta Cemeteries: St Patrick’s. Parramatta and District Historical Society, 1988, p. 10.

[3] Suters Architects Snell Pty Ltd. St Patrick’s cemetery: conservation plan (1995), p. 15.

[4] Catholic Church, St Patrick’s Cemetery, Parramatta: Cradle of faith, grave of the faithful. Parish of St Patrick’s Parramatta, 1994, p. 3.

[5] Fatal stabbing case in Parramatta Gaol. (21/01/1876). The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 2. Retrieved on 29/06/2021 from https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/

[6] Mak Sai Ying aka John Shying. (2017). Retrieved on 29/06/2021 from

https://historyandheritage.cityofparramatta.nsw.gov.au/people/mak-sai-ying-aka-john-shying

[7] Catholic Church, St Patrick’s Cemetery, Parramatta: Cradle of faith, grave of the faithful. Parish of St Patrick’s Parramatta, 1994, p. 9.

[8] Electrocuted. (02/10/1923). The Daily Telegraph, p. 5. Retrieved on 30/06/2021 from https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/245994896

[9] New Mortuary Chapel. (28/08/1844). Morning Chronicle, p. 2. Retrieved 26/04/2021 from https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/31743450

[10] Catholic Church, St Patrick’s Cemetery, Parramatta: Cradle of faith, grave of the faithful. Parish of St Patrick’s Parramatta, 1994, p. 7.

[11] Information on Anne Faye. Retrieved on 07/07/2021 from https://australianroyalty.net.au/tree/purnellmccord.ged/individual/I49106/Anne-Faye

[12] Information on William Bellamy. Retrieved on 07/07/2021 from https://australianroyalty.net.au/tree/purnellmccord.ged/individual/I49105/William-Bellamy

[13] State Archives and Records NSW, Registers of Certificates of Freedom, 4 Feb 1810 - 26 Aug 1814: Ann Fay.

[14] Catholic Church, St Patrick’s Cemetery, Parramatta: Cradle of faith, grave of the faithful. Parish of St Patrick’s Parramatta, 1994, p. 9.

[15] Death of a police office. (25/10/1873). The Freeman’s Journal, p. 10. Retrieved on 30/06/2021 from https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/128809284

[16] Details for Catherine Magdalene Kelly. Retrieved on 06/07/2021 from https://austcemindex.com/inscription?id=9338454#images

[17] Parramatta Heritage Centre & Casey and Lowe. 2009. Breaking the shackles: Historic lives in Parramatta’s archaeological landscape. p. 35. Retrieved on 30/06/2021 from https://caseyandlowe.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/breaking_the_shackles.pdf

[18] Advertisements. (09/09/1820). The Sydney Gazette and NSW Advertiser, p. 4 Retrieved 07/07/2021 from https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/2179738

[19] State Archives and Records NSW. Colonial Secretary Correspondence, John Hodges of Parramatta: Received Ticket of Leave. 24 July 1813, Reel 6002.

[20] State Archives and Records NSW. Colonial Secretary Correspondence, John Hodges: House at Parramatta to be valued in connection with his claim for a grant of the premises, 6 & 10 December 1823, Reel 6011, p. 664 & Reel 6059, p. 109.

[21] Brislington Medical and Nursing Museum. (2020). Retrieved on 06/06/2021 from https://historyandheritage.cityofparramatta.nsw.gov.au/blog/2020/03/23/brislington-medical-and-nursing-museum

[22] Notice of Pardons. (19/03/1841). NSW Government Gazette, p. 2. Retrieved on 06/07/2021 from https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/1286832